By Candy Martínez, Ph.D. Candidate in Latin American & Latino Studies ~ UC Santa Cruz

Going to Oaxaca to conduct field research has consisted of an exploration of different climates, altitudes, languages, tastes, sounds, and colors. Beyond the timeless Oaxacan landscapes filled with rolling green hills, resilient magueys, and ancient cacti, are the contemporary cultural practices and epistemologies influenced by Western religions, passed-down traditions, and intercultural exchanges. In part because of its cultural and natural diversity, I have chosen to research the multiple forms for understanding emotional pains (including susto/fright, profound sadness) and healing in Oaxaca. In this research experience, I have come to appreciate the importance of communication, gozona (the Zapotec term for mutual aid), convivenza (coexistence or living together), patience, and respect whenconducting research on a sensitive topic.

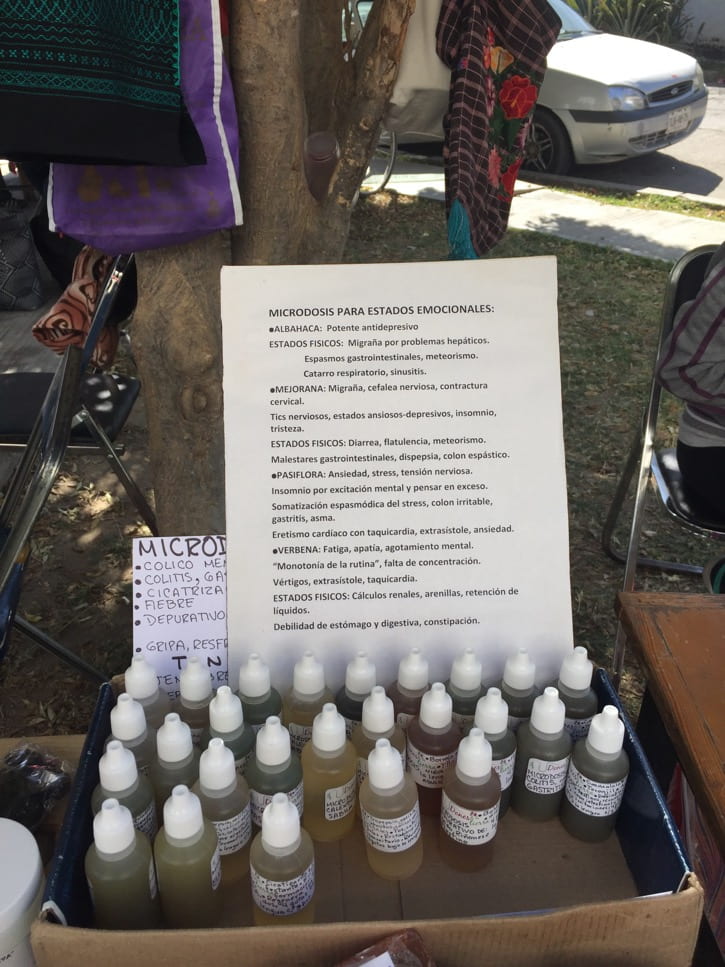

As the daughter of Oaxacan indigenous migrants, I have reconnected to my roots. And as a new researcher in Oaxaca, my journey has taught me some valuable lessons about communication and forming meaningful relationships in the field. I have learned about the words and meanings used to discuss susto, sadness and trauma in Zapotec. For instance, in San Juan del Río, susto is pronounced as “jeeb,” in San Dionisio Ocotepec it is pronounced as “jeebi,: and in San Juan Tabaá, susto is pronounced as “chebe.” I have also learned about the medicinal plants used to heal emotional pains and their symptoms from elderly people. I have detoxified my body with local healing herbs during temazcal baths and limpias (spiritual cleanses) such as chichicastle, rue, and pirul. Though there are aspects of my research that I find nourishing, there are also moments that are difficult to process. I have listened to stories of not only familial separations, but also of elderly abandonment, gender violence, witnessing of violence in one’s community, and sudden deaths.

A generational tension exists in Zapotec and Mixtec communities about cultural traditions. Youth in particular shun traditional practices and view

susto rituals as being done by “less civilized” people. Internalizing these negative views informs the way many Oaxacans continue to understand emotional pain. Yet, Oaxacan musicians, artists, and filmmakers insist that one focus on emic perspectives of emotional pain; that is, they

stress the importance of understanding sadness, trauma, emotional suffering from the narratives of indigenous communities.

From music by the Mixtec Pasatono orquestra to the Illuminarte gallery exhibition in Huajuapan de León about profound sadness, and the fictional films regarding tiricia (sadness embodied as a malady) directed by Ángeles Cruz and Jorge Pérez Solano,

honoring traditional forms for understanding emotional pain has led to an important emergence of cultural expressions. These cultural efforts focus on how the way emotional pain of Oaxacan indigenous communities intersects with migration, family conflict, gender violence, and alcoholism.

My research observations led to me ponder a number of questions: What can we learn from the histories, testimonies, and knowledge from diverse and resilient Oaxacan communities in regards to processing pain and healing? And how can we apply this wisdom to an era when stress and emotional pain only seems to be increasing, and especially affecting migrants and working-class communities throughout the world?

Understanding the sensitivity of my research project, I knew I had to be thoughtful when recruiting prospective interviewees. I posted flyers throughout Oaxaca about my study and organized film screenings regarding my research topic. Though I connected with handful of people that way, I knew I needed to reach more people. I approached civil society organizations in Oaxaca that provide legal and psychological resources to indigenous and/or working class communities such as: Mano Vuelta A.C., Nosotras Libres A.C., and Consorcio para el Diálogo Parlamentario y la Equidad Oaxaca A.C. I also found public educational spaces, hosted by Universidad de la Tierra and Servicios Universitarios y Redes de Conocimientos en Oaxaca (SURCO) A.C., as important sites to locate individuals interested in my research. I discovered that networking with individuals in multiple places was instrumental for my research process. Additionally, I met community leaders, received invitations from individuals to their community and, in some cases, had an opportunity to conduct in-depth research interviews.

2018.

FILMUFE (Feria Internacional del Libro de Estudios de las

Mujeres, Feminismos, y Descolonización) Initiation Ritual

and Offering to the 4 Cardinal Directions, May 5, 2018.

Interacting and networking with people in Oaxaca does not simply consist of exchanging a phone number and meeting someone once or twice over coffee; rather, it often requires one’s enactment of gozona, the Zapotec term for mutual exchange and active involvement. I have attempted to do my gozona by volunteering for events open to the public organized by the International Book Fair on Women, Feminisms and Decolonization (FILMUFE), Ojo de Agua Comunicación, Nosotras Libres A.C., Consorcio Oaxaca A.C. Though the act of doing gozona does not automatically entitle me to obtain information for research purposes, it certainly brought forth solidarity.

By forming these types of relationships as part of my research, I obtained important insight about my research process. For instance, I incorporated the feedback from individuals who stressed how indigenous communities use Zapotec and Mixtec words, not just “tiricia” (a word known in some communities in Mexico to describe profound sadness) or “trauma,” to discuss profound emotional wounds. Talking with Oaxacan community leaders, such as Meliton Bautista, allowed me to consider how a Spanish translation of a Zapotec word should not just be taken literally. Bautista takes into account how deciphering Zapotec words relies on understanding and unpacking Zapotec cosmovisions, which are not so easily translatable linguistically. To unpack Zapotec meanings, Bautista emphasized learning the histories of the communities themselves. Even though this delayed my research in some ways, these suggestions were crucial to incorporate for the integrity of my research project.

As a new researcher, I learned to not underestimate the value of convivendo, especially in small communities where I conducted my interviews. Conviviendo for me entails more than simply spending time with individuals but rather, eating, dialoguing, reflecting, listening and sharing stories with those around me. The act of conviviendo has allowed people to get to know me and learn about people who could enhance the research. Conviviendo has provided me with a holistic lens of how Oaxacan towns are situated geographically, culturally, economically, and linguistically.

The research process has challenged me to not make assumptions about what I think is happening in these communities. For example, not all individuals will claim that their communities experience social injustice or inequality, even if national surveys, administered by the Secretary of Social Development (SEDESOL) regarding poverty and social risk, may indicate otherwise. Not all historical events may impact a small community and the individuals who reside in such community in the same way because factors such as social status, language, familial support, and community roles influence whether or not individuals can overcome or emotionally struggle with past catastrophic events. In addition, the presence of a couple of curanderas/os in a community or a large presence of inhabitants who speak an indigenous language in Oaxaca does not mean that most individuals in this community continue to practice rituals for healing sadness or susto, which has been the case in San Juan del Río, Tlacolula, a Zapotec community with a high percentage of migration. Several individuals there notified me many individuals do not participate in rituals associated with healing sadness or susto because their religion forbids it. I discovered that the preservation of traditional healing practices may be more influenced by religious beliefs than their conservation of indigenous native language.

Offering Ritual on a hilly shrine in Mitla, Oaxaca, April

14, 2018.

New Directions and Possibilities for My Research

Colectivo Mujer Nueva Tianguis in Centro Cultural y de

Capacitación de la Sección 22 (CEPOS), March 11, 2018.

My research aims to analyze how and why healing rituals allow Oaxacans to begin articulating and embodying their emotions in ways that they cannot do during a medical or psychological consultations. Several psychologists in Oaxaca encourage the open discussion and practice of these healing rituals for their patients as an entry point to receive the necessary psychological therapy. I have begun to interview medical doctors (a suggestion I received from a migration specialist) and have questioned why doctors report it is not common for individuals to discuss their emotional pain with them. The research of Paola Sesia, a Mexican-based medical anthropologist, describes how public health services can be insensitive and discouraging for Oaxacan citizens. My interviewees, specifically teachers and psychologists, suggest children and adults have a difficult time discussing their emotions with others, including their family members. Multiple factors may account for this almost absent presence of individuals who discuss their emotional pains to doctors.

Age has ended up being an important factor in considering the existence of emotional pains within Oaxacans. The small group of individuals who seek advice from doctors for psychological or emotional distress in rural communities tend to be elderly people who are missing their children in the United States. Doctors report that elderly people not only experience profound sadness but also abandonment by their children. These doctors’ statements resonate with the interviews that I conducted in communities where there is a high percentage of migration to the United States. Elderly people are especially vulnerable to exhibiting profound sadness, excessive worry, and/or susto because their children have migrated. This discovery means my research will now examine how age impacts one’s susceptibility to emotional pain.

I believe I have become a better researcher by not underestimating the value of respect whether with potential interviewees or the communities where I plan to conduct additional interviews. During the beginning of my research experience, I made sure not to rush into conducting interviews right away. Not being from Oaxaca, I wanted to get to know individuals and civil society organizations first. Further, it was important for me to consider historical events, economic conditions, natural resources, languages practiced, cultural and people’s faith(s) so that I would not essentialize indigenous Oaxacan communities. Oaxacans learn about healing methods and remedies through elderly family members, transnational healers, and through non-traditional resources (books, workshops, trainings). When it comes to conducting interviews, patience has been key. As a graduate student who is under pressure to write and produce within a certain time frame, it has been refreshing for me to let my research interviews flow, to respect people’s time even if it means long delays and to respect the energy it takes to answer loaded questions such as, “What does healing mean?” Rather than providing me with encyclopedic-like responses, my interviewees often provide me with anecdotes or examples thus inviting me into their worldviews. Approaching my research with an open mind and an open heart have been some of the most important lessons that I have gained as a new researcher.

Capulli Traditional Healing Center in Capulalpam de

Méndez, Oaxaca, September 26, 2018.