By T. J. Demos, Professor of History and Art and Visual Culture, Director of Center for Creative Ecologies ~ UC Santa Cruz

How has Zapatismo—the militarized Indigenous Mayan formation based in the highlands of Chiapas—fared after more than a decade of self-declared autonomy? How has the movement survived a Mexican state witnessing growing devastations of organized crime, government corruption, paramilitary violence, and narco-trafficking since its founding as the EZLN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) in 1983?

As well, what has the expanding reach of Facebook and Twitter in the era of anti/social media meant for the movement that has from its beginnings represented an exemplary model of digital decoloniality? And while it’s political organization has long been celebrated for integrating women (1) in leadership positions (for instance, its Juntas de Buen Gobierno), what is the status, if any, of queer and trans-Zapatismo, of non-heteronormative collectivization? Relatedly, what does it mean for the movement’s commitment to autonomy that it supported the running of Marichuy, traditional healer and long-term feminist and human rights champion, representing the National Indigenous Congress in the recent presidential election that ultimately saw the progressive win of Lopez Obrador?

These were some of the pressing questions on my mind as I set to participate in the inaugural collective residency of GIAP (Grupo de Investigación en Arte y Política), based in San Cristóbal de Las Casas during July 2018. Founded in 2013 by Chilean art historian Natalia Arcos and Italian sociologist Alessandro Zagato, GIAP comprises a research collective dedicated to the study of the aesthetics and politics of contemporary Latin American autonomous formations. They publish essays, maintain a website and blog, and curate exhibitions. During this last summer they have begun opening their space to two-week long gatherings hosting international artists and researchers. The one I participated in (and acted as co-director) was dedicated to “Creative Ecology and the Aesthetics of Autonomy”; this upcoming November, they have a program entitled “In (Self-)Defense of Giraffes: Arts and Resistance in Chiapas,” borrowing its wording from a communiqué written by Subcomandante Marcos in 2004. This last summer’s residency represented an intensive collective un/learning project in Spanish and English undertaken with nine other participants, generally multi-disciplinary artists coming from places as diverse as Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, the Netherlands, and the US. My experience overall was extremely positive.

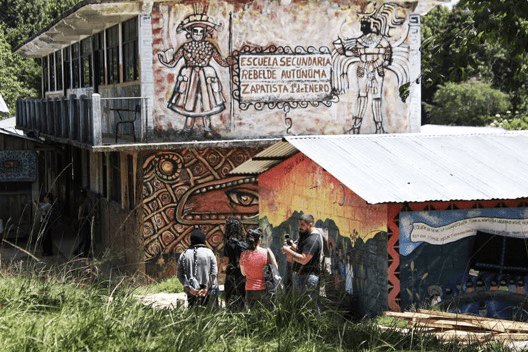

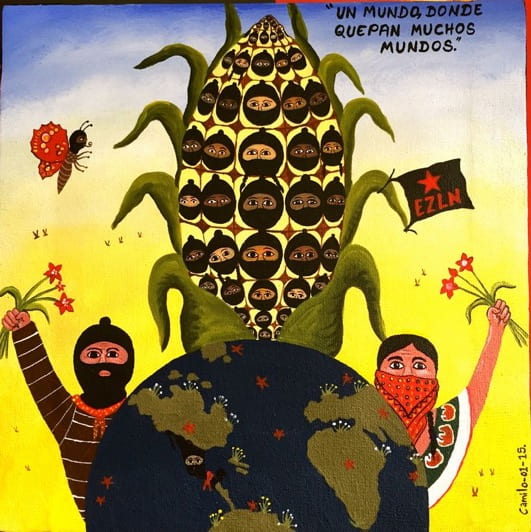

The residency began with a series of intense seminars led by Arcos and Zagato on the history of Zapatismo, providing an introduction to the movement’s political motivations and an overview of its watershed moments. These included the EZLN’s militant origins in anti-colonial and anti-capitalist opposition; its 2006 Other Campaign, when the leadership traveled across Mexico meeting with trade union organizers, Indigenous leaders, and women’s rights and LGBTQ activists, the goal being to “listen” to those who also struggle; its 2012 March of Silence, when, in an unannounced show of organizational force, thousands of EZLN members filed into the central squares of such Chiapas cities as San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, Comitan, and Altamirano, without uttering a public word, and thereby contesting media misrepresentations (“to be heard, we march in silence,” read a subsequent communiqué); and its recent series of “escuelitas” and arts festivals, whereby the movement has engaged its own pedagogy of the oppressed, forged alliances with other international rebellions, and organized discussions of science as a tool of resistance, of Indigenous feminism, and of the role of the arts in creating “un mundo donde quepan muchos mundos” (a world in which many worlds fit), as explains one of the movement’s many poetic slogans bearing cosmopolitical significance. Following these first couple days of group study and discussion, we visited the Oventic “caracol,” one of five Zapatista political centers, about an hour from San Cristóbal, and named after the slow-moving, deliberate, spiral-shaped snail shell. Zapatista culture, like any other, is far too complex and nuanced to simply, or ever, reveal itself before the ethnographic gaze—and none of us had this expectation (indeed, the Zapatistas regard researchers guardedly, understandably, given past distortions of the movement). We still learned a lot from our visit, and it was moving to see first-hand the beautiful mural decorated buildings, organizational spaces, and school buildings, as well as the agricultural fields, of the Oventic complex, which was generously introduced to us by two Tzotzil-speaking balaclava-clad women (representatives of their respective villages staying temporarily at Oventic while they perform their political service). The prevalence of corn, the central crop for the Zapatistas, was ever present in the caracol’s gardens and visual culture. Grown without chemical inputs or biogenetic engineering, maize both offers a staple food that is a central figure of resistance to NAFTA imports that have devastated small-scale and subsistence farmworkers in Mexico (owing to their cheap, state-subsidized and biogenetic production in the US), and defines a primary source of identification and reverence for Indigenous folks in this region. A related visit took us to Otros Mundos Chiapas, situated in the mountainous outskirts of San Cristóbal, where we were offered a tour of the organization’s amazing low-impact architecture (using adobe design, green roofs, passive solar, and recycled materials). It figured as a powerful symbol of living otherwise, standing in stark contrast to the projects of green capitalism, extractivism, and techno-scientific engineering, which the group opposes in its educational and networking activities.

San Cristóbal de las Casas

Over the course of the two-week residency, participants debated many unresolved questions about Zapatismo. One topic of discussion was the EZLN’s military discipline, necessary to the movement’s defense against state violence, which the Zapatistas connect to 500 years of colonial oppression, and which continues in ongoing paramilitary attacks carried out in defense of extractive projects and land grabs. (Indeed, our group also visited a commemorative ceremony in nearby Acteal, where the paramilitary Mascara Roja massacred 45 Indigenous folks in 1997, in part because their pacifist group Las Abejas, the bees, professed support for the EZLN). Does Zapatista regimentation—clear in the masked faces of members—erase individual freedoms and expression, constituting a form of Leftist oppression, we wondered? It was pointed out, alternately, that western capitalist individuality is itself a mode of authoritarianism that tends to negate collective empowerment, self-determination, and political formation, all clear in the history of Indigenous dispossessions, biopolitical social controls, and technologies of atomization. While the EZLN has never called for an expansion of their specific modes of resistance—instead, encouraging the formation of transnational alliances adapted to and addressing their own singular local conditions—militarization appears to act less as an oppressive force than a necessary formation of collective emancipation supporting Zapatista autonomy within its own specific geopolitical context. Still, the movement is far from perfect, and has always acknowledged ongoing challenges and contradictions—as they say in another of their mottos: caminando, preguntamos, “walking, we ask questions.”

We also considered the question of Zapatista identity—who can be a Zapatista? The movement has approximately 300,000 members, the vast majority of whom are Indigenous Mayans living across Chiapas. While welcomed openings exist for transnational alliances and solidarities, its membership is exclusive to Indigenous communities in this region. Zapatismo, in other words, is neither multicultural nor postidentitarian per se, but rather tied to Indigenous survival. As such, anti-essentialist critiques become incomprehensible in this context, even potentially risking a neo-colonial logic of disruption, especially where those critiques confuse revolutionary subjectivity with an immutable native identity never claimed by the EZLN in the first place. What about social regimentation in gender/sexual terms, where one might suspect Zapatismo as being heteronormative and patriarchal—what of the possibility of a queer or trans Zapatista, or gay marriage (now legal in much of Mexico)? Perhaps the best quote is from Sub Marcos, reflecting on his own illusive figure as a site of diverse identifications, ultimately dissolved in 2014 as an unproductive media distraction, when Marcos became “Galeano,” named after a Zapatista killed by paramilitary forces earlier that year: “Yes, Marcos is gay. Marcos is gay in San Francisco, Black in South Africa, an Asian in Europe, a Chicano in San Ysidro, an anarchist in Spain, a Palestinian in Israel, a Mayan Indian in the streets of San Cristobal, a Jew in Germany, a Gypsy in Poland, a Mohawk in Quebec, a pacifist in Bosnia, a single woman on the Metro at 10pm, a peasant without land, a gang member in the slums, an unemployed worker, an unhappy student and, of course, a Zapatista in the mountains.” While that quote is impressive, we didn’t have much opportunity to measure its operation in Zapatista communities—though we did hear about how local governance provides a fair and open process for conflict resolution, should any form of discrimination arise.

As to patriarchal authority within the movement, it was notable that the National Indigenous Congress chose a Nahua woman to run in the recent presidential election, though Marichuy’s candidacy failed to gather enough signatures and was overcome—in part by alleged voter disenfranchisement practices—by widespread support for Lopez Obrador, nonetheless himself a figure of progressive hope for Mexico. What this means for movements of Indigenous autonomy historically opposed to electoral politics is still unclear and will be contemplated further by the EZLN in coming months and years. It was fascinating for us to collectively consider the notion of autonomy in relation to artistic practice. Historically in the West it’s been fetishized as individual creativity, reinforced by education, and commodified by markets, museums, and galleries that celebrate and reward exemplary subjects with monographic exhibitions and publications. Yet in the highlands of Chiapas, autonomy is collectively articulated, meaning that aesthetic values and meanings, stories and representations, are produced by and through Zapatista communities. Even while individual artists may arise as noteworthy—such as Zapatista painter Camilo, as he is known by his pseudonym—and sell their work on tourist markets (as in shops throughout touristy San Cristóbal), the visions, stories, slogans, and proceeds are defined, discussed, and shared collectively.

On another day, we visited the beautiful campus of “Unitierra,” the University of the Earth and platform of CIDECI (Centro Indígena de Capacitación Integral), on the outskirts of the city, where it forms part of the movement for autonomous learning that began in Oaxaca, Mexico with Gustavo Esteva. Unitierra holds a weekly free seminar that discusses current events and political theory, beginning with introductions in Spanish, Tzotzil, and Tzeltal, before turning to open conversation. Practicing the “deprivatization of the

imagination,” it offers courses in language, agro-ecology, anti- and de-colonial political philosophy, music, mechanical engineering and more, requiring neither entrance exams nor tuition, and works closely with Indigenous communities in the area including the Zapatistas, with whom it’s allied. Unitierra offers an intriguing model of what a Zapatista university might look like, and indeed the movement is looking to create such institutions within its own Lacandan forest territories.

The residency also included the guest visits of Francisco Huichaqueo, Mapuche artist from Chile, and Tsotsil documentary filmmaker María Sojob. Both offered further examples of the practice of Indigenous autonomy, where both Huichaqueo and Sojob have experimented with the construction of creative artistic individuality that operates in synergy with traditional communal ties. This involves inventing cinematic forms and archival systems that recover collective memory, translate Indigenous experience, and resist ongoing modes of representational and material erasure.

Huichaqueo discussed the Mapuche struggle against hundreds of years of colonization, followed by the military dictatorship and authoritarian neoliberalism of Pinochet, as well as current prospects for land reparation and autonomy for Indigenous people in Chile. In 2015, he was invited to curate an exhibition at MAVI, the Museum of Visual Arts in Santiago, and his project, carefully developed with Mapuche elders, was sourced in the artist’s dreams. It led to a presentation of Indigenous objects positioned as if swirling around the gallery, many of them artifacts reclaimed from anthropology and reanimating an imagined Mapuche dreamspace (including a traditional flute that was played for the first time in more than a hundred years after being entombed in the museum’s archive). The artist also created a series of videos foregrounding Mapuche stories, and organized extensive community-directed public programs.

Meanwhile, Sojob—who along with Huichaqueo studied in Santiago de Chile with the legendary Chilean documentarian Patricio Guzman—discussed her challenging negotiation of western film conventions and Tzotzil cultural sensibilities, which has resulted in Sojob’s indigenization of documentary practice. Her own modeling of a Tzotzil cinema includes the expression of the aesthetics of “lekil kuxlejal,”2 the Tzotzil name for buen vivir (also emerging in the Andes as sumak kawsay in Quechua), referring to the community practice of “good living” that privileges collective care and ecological responsibility, alternative to western competitive individualism, wealth accumulation, and destructive extractivism. Her cinematic focus on family residing in rural Chiapas practicing organic agriculture, low-impact living, craft-based weaving practices, and enmeshed in multispecies relationalities, gave powerful filmic sensibility to this form of life.

How might Zapatismo extend and inspire cultural practices and anti-capitalist rebellions beyond the Chiapas highlands? The residency also considered a range of radical artistic-activist formations in places as diverse as Cuba, Russia, and England, offering further examples where collectives, such as Chto Delat from St. Petersberg, have developed projects, including an exhibition in Mexico City in 2017, drawing part inspiration from the EZLN; or when former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party Emory Douglas visited Chiapas to create murals mixing Zapatista themes with Panther revolutionary visual culture, leading to a book publication in 2017. Our residency finished with a Skype discussion with ATA, meaning “them” in Albanian, naming a collective based near Tirana. The group of artists, poets, and actors engages the Zapatistas’ poetics of liberation, which, along with the radical pedagogy of Paulo Freire and the rebellious theater of Augusto Boal, offers powerful resources for the group’s attempts to inspire revolutionary resistance to the tide of neoliberalization that has overtaken this erstwhile Stalinist dictatorship. The question of translation consequently came to the fore: how to bring the radical aesthetics and politics of Latin America to contexts such as this with well-justified suspicions of Left-wing revolution that has until the late ‘80s only delivered violent state oppression, material austerity, and the double-colonization of Soviet and elite Albanian rule? In the end, if these and other questions remained only partially addressed, the GIAP residency nonetheless went a long way in discussing them. To witness how expanding movements for Indigenous autonomy are turning into thriving multi-generational cultures with politico-ecological resilience and ongoing internal development was impressive—and for more info, check out the various EZLN social media platforms. Ultimately it was deeply inspiring to participate in this transnational networking of radical aesthetic and political projects during those two intense weeks in Chiapa

- See Siva Vaidhyanathan, Antisocial Media: How Facebook Disconnects Us and Undermines Democracy (Oxford: Oxford University 1

Press, 2018). - See Mariana Mora, Kuxlejal Politics: Indigenous Autonomy, Race, and Decolonizing Research in Zapatista Communities (Austin: University of Texas, 2018).