By Bristol Cave-LaCoste, Ph.D. Candidate in History and Designated Emphasis in Latin American & Latino Studies ~ UC Santa Cruz

Bristol Cave La-Coste speaking about her research at

the RCA Student Forum, Santa Cruz Museum of Art &

History, April 26, 2018.

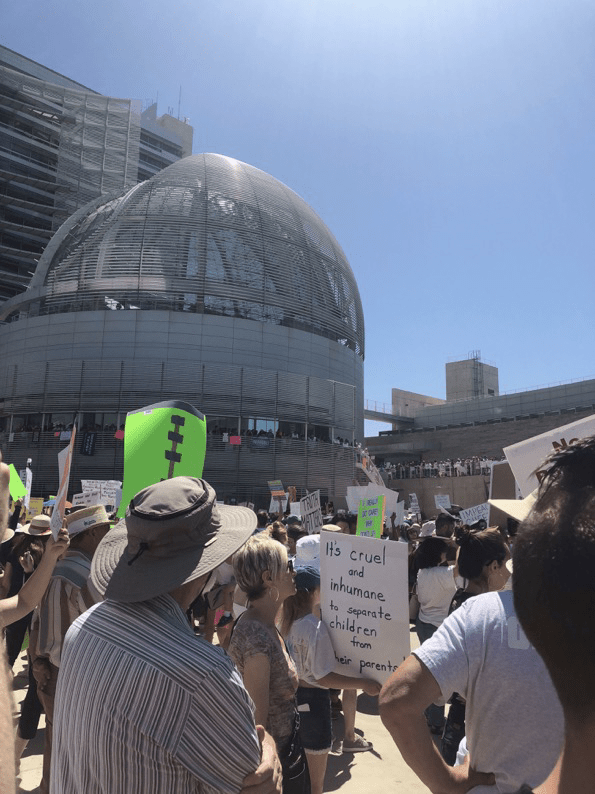

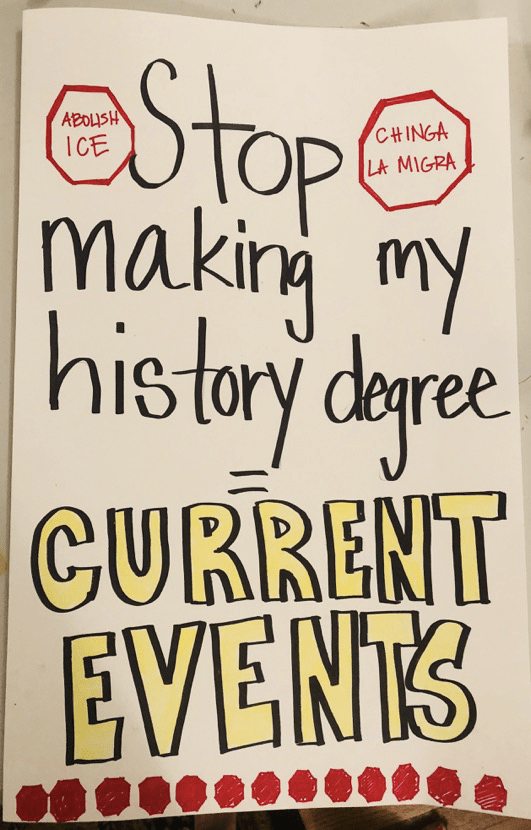

On June 30, 2018, tens of thousands of people across the United States gathered to protest the horrendous detention and separation of immigrant families, a practice accelerated under the Trump Administration. Over the previous weeks, journalists brought us images and reports of children, mostly Central American, eligible for refugee status and protection yet were being forcibly separated from their parents, incarcerated, neglected, and, as journalists would subsequently report, abused in multiple ways. All of this cruelty happened at the hands of the U.S. government. I joined a crowd of one thousand at San José City Hall with a homemade sign that said “Stop making my history degree into current events.” When I started my Ph.D. in History at UC Santa Cruz four years ago, I appreciated the bit of emotional and intellectual distance history allowed. History resonated with me personally, but I had not yet realized how much it would echo the world around me. Often I wish it did not. As I dig into several more years of research at the National Archives and Records Administration for my dissertation about the role of sexual policing and anti-prostitution campaigns in early federal immigration law, I am confronted with messages from the past that deserve more attention in the present. It is imperative that more of us listen and follow the lead of immigrants who have been fighting racist, unjust U.S. administrations long before 2016. As the historical record reveals, marches and rallies cannot be the only strategy of resistance.

To describe our current political moment as unprecedented or dystopian feels lacking. I don’t disagree entirely but, as a historian, I know that so many of the same sentiments – of nativism, dread, or frustration with unbridled capitalism – date back more than a century ago. Theodore Roosevelt, U.S. President from 1901 to 1909, was considered a model of bipartisanship and reasonable reform, but often lamented the “race suicide” of Anglo-Saxons in America, whom he believed would soon be outnumbered by more “fertile” immigrant families. Roosevelt appointed nine politicians and social scientists for the Dillingham Commission from 1907 to 1911 to study the problems of immigration. Though they found that unsafe housing, exploitative working conditions, and social barriers to assimilation were at fault, they recommended more stringent exclusions of “undesirable” immigrants instead. If published today, their 41-volume study could probably be successfully re-packaged as a Twitter storm.

Protest in San José against family separation, June 30, 2018

As a historian of U.S. immigration, I can’t help but see today’s crises as maddening proof that our immigration policies are operating exactly as intended – as inhumane and xenophobic. Clear evidence of the injustices perpetrated in catastrophic moments abound, like the forced deportation of up to two million Mexicans and Mexican-American citizens during the Great Depression between 1929 and 1936, or the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II under xenophobic claims of national security. These examples should serve 1 to caution us: removing one person, or even one political party, from the power that comes with being part of the U.S. government, will not automatically improve the system.

The historical examples discussed above are apt, but they also don’t tell the full picture of how and why immigration policies remain so harmful. Since the time of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, day-to-day immigration operations have deliberately worked in secrecy, with minimal public transparency or checks and balances from other branches of government. Migrants, immigrants, and refugees have been routinely stripped of the rights and legal representation afforded others, despite many constitutional protections being promised to citizens and non-citizens alike. From the 1875 Page Act and to the 1924 National Origins Act, policies routinely categorized and punished immigrants according to race, class, health, gender, political affiliation, education level, morality, and other perceived traits or allegiances. Immigration agents alone defined these categories and assigned them to those migrating, with little hope for migrants to appeal these appointed categories. At times, public opinion supported such exclusions, but in many cases the public could not have seen the totality of the immigration system. But today, we are seeing what the immigration system has always done to migrants – institutionalized racial terror and fear.

Many activists and other concerned citizens speak of the need for resistance when it comes to the devastating actions of the Trump Administration. Resistance too has a rich history, though the term has been used somewhat differently by historians for decades, as a way to identify how individual historical figures might have knowingly or subconsciously fought back against their own oppression. Understanding the complexity of the past, its oppressive institutions and everyday resistance, suggest tools for confronting similar institutions in our own time.

How did immigrants survive this dehumanizing system? Immigrants challenged the conditions set by immigration regulation and rejected the narratives of their own criminality, inadequacy, or difference. Some of this resistance traveled through formal channels, especially through court cases. In fact, so many court cases resulted in favor of immigrants that the Bureau of Immigration worked to reduce immigrant access to due process and further conceal their policies from judicial admonition. But even beyond organized, well-funded forms of resistance were everyday acts of non-compliance that showed the risks immigrants and their allies would take for the right to migration. Agents on Angel Island outside San Francisco once confiscated a banana whose peel was glued shut to conceal a wadded-up map and coaching notes a Chinese immigrant used to prepare for interrogation; cafeteria workers were at times punished for supplying such food-borne aid. At the El Paso Immigration Station in 1917, 17-year-old Carmelita Torres incited her fellow border-crossers to refuse the mandatory spray-down with gasoline intended to kill lice and “disinfect” migrants, many of whom crossed daily for work. The migrants marched through town demanding the end to the humiliating and dangerous baths until Mexican and American soldiers quelled the protest. Torres was arrested and the practice continued through the 1960s but the “Bath Riots” show that non-compliance could be spontaneous, led by an outspoken working-class woman, and rejected both specific policies like the baths and the racist narrative of dirt and disease they perpetrated.

In my own primary source research, resistance is sometimes harder to find, but it is there. I focus on cases of exclusion or deportation based on accusations of prostitution, which was one of the earliest categories for immigrant exclusion beginning in 1875. The social stigma of sexual nonconformity further reinforced the practice of criminalization in the immigration process. A woman could be labeled a prostitute for being caught kissing a man she was not married to; for being found wandering too close to a military base; or even for having a childless or non-traditional marital arrangement. The definition of prostitution and “other immoral purpose” was so slippery, it was hard for a woman to fight the proceedings. Besides false accusations, some immigrant women did participate in sex commerce for their livelihood and believed they deserved a place in the United States like anyone else. Their American clients certainly hadn’t protested their presence and did not face arrest or deportation. Sexual policing affected all immigrant women by sending the message that to be an American meant submitting to an impossibly narrow Protestant Christian

sexual standard.

Sign created by Bristol for protest in San José.

Yet immigrant women did not always accept these boundaries. In February of 1890, Mok Jow Yee was interrogated by U.S. officials along with a few dozen other Chinese women seeking entry to San Francisco. Like many others migrating during the 5 Exclusion era, Yee claimed to be born in the United States and therefore entitled to (re)enter the U.S. This claim led to aggressive questioning regarding her childhood memories, family connections to the United States, and her husband’s employment prospects. The questioning agent strongly insinuated that her husband was lazy and looking to take advantage of her parents’ money and her own income as a seamstress, a red flag that he might plan on selling her into prostitution. Yee did not take the bait. For several pages of the transcript she answered each speculative question by flipping the question itself. Although her words on the page were translated from her native Cantonese by a white American agent, bold assertions of self-worth stand out.

“Q [Agent Schell]: Who told you you could have your

husband arrested if he wanted you to do that?

A [Mok Jow Yee]: Well I know that nobody can force

me to be a prostitute. I know I can have him arrested.

Q: Who told you that?

A: Do you not suppose that I know that?”

The interrogation continued for several more pages of sharp responses, culminating in the agent’s final remark that Yee must have been forced to come (or return) to the United States against her will. Her response is notable: “If I did not want to come I would not have come. If I did not want to have come I would not have gone on board the steamer and got as seasick as I did and all that trouble for nothing. If my husband tells me to do anything I will do it if it is right. If it is not right I will not do it.” Yee took clear ownership of her own migration and her ability to make ethical decisions for herself, countering the common narratives of the time about Chinese women as passive followers of familial orders. The tone of the transcript suggests her technique surprised and frustrated the immigration agent. Yee might not have seen her words as a brave act of resistance, but her responses reflect a courage that is part of resistance. She certainly did not comply with an immigration system established to intimidate women. But what is the value of Yee’s non-compliance?

Unfortunately, I do not know if Yee’s testimony paid off for herself. Although on paper she appears to have weathered a particularly long and grueling interrogation, her case does not have any notations about whether she reunited with her husband in San Francisco or was sent back to China. However, I hold on to hope for Yee and others for whom the record becomes murky – sometimes the best survival comes from disappearing from the record altogether. Perhaps she attempted another entry under fake identification papers; perhaps she found a way to cross into the United States from Mexico or Canada. It’s possible that her husband really was lazy and an unpleasant spouse, whom she could now sever ties with. We can’t know for sure, but the narrative that exists on paper suggests that some Chinese immigrant women rejected the messages put forth about them and fought to make their own way in a hostile world.

I believe the defiant words of women like Yee are meant to motivate us in the present, not be kept behind glass and in archives. Stories like this reminds us that immigrants have fought, and continue to fight for justice with the tools they have, even when their losses can be devastating. It is not immigrants’ responsibility to fix the system that seeks to diminish them; it is our collective responsibility to end a system that has gone on far too long. Agencies like U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (I.C.E.), formed in

2003 to extend federal immigration authority as a matter of “national security,” must be dismantled so thoroughly that they cannot resurface out of public view. As we confront the current realities of forcible family separations, of the actions of a U.S. government so reckless and cruel that parents have been deported and children are being detained in the United States, of the flippant manner in which U.S. authorities talk about all immigrants as criminals, we have no choice but to engage in acts of non-compliance and support the actions of immigrants themselves who are, as they’ve done in the past, using the judicial process to assert their rights, and engaging in bold acts of political protest such as hunger strikes.

Footnotes

- For more on these crises and grassroots resistance to them, see Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodriguez, Decade of Betrayal:

Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2006); Takashi Fujitani, Race for Empire:

Koreans as Japanese and Japanese as Americans during World War II (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); Cherstin Lyon,

Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory (Philadelphia: Temple

University Press, 2011). - Lucy Salyer, Laws Harsh as Tigers: Chinese Immigrants and the Shaping of Modern Immigration Law (Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

- Erika Lee and Judy Yung, Angel Island: Immigrant Gateway to America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- I use “prostitution” as a historically-situated and legal term in my own work, although for the contemporary moment “sex work” is the more appropriate term.

- File 9270/69, Box 17, Records of the INS, Immigration Arrival Investigation Case Files, 1884-1944, RG 85, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), San Bruno, CA